FIGURE 1 | Reflective space – Church grounds. Pen and watercolour on paper. Ange Morgan 2016

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2018) 4(2):214–224 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2018/4/32 |

Art Making Through Change: New Journeys with Gender and Identity

La Trobe University, Australia

Abstract

This paper discusses the role of the art making process within art therapy to support experiences of change, loss, and new identities, where themes of social change, pioneering and new narratives create challenge and opportunity for those within the therapeutic art making space. The paper discusses a heuristic art-based process, and examples and considerations for art therapy group work practice in relation to gender transition, and non-binary identity.

Keywords: transition, non binary, group process, art making, social change, disclosure

Prior to, and increasingly since the Australia Marriage Law Postal Survey in 2017, which resulted in a majority Yes vote to enable same sex couples to marry (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017), there has been considerable challenges and advances in awareness, inclusion, and development of best practice care for people from the trans and gender diverse (TGD) communities in Australia (Australian Healthcare Associates, 2018; Brown et al., 2018; Riggs & Due, 2013; Telfer et al., 2015; Victoria State Government, Department of Health, 2018). Alongside this there has been a call to develop workplace (Brown et al., 2018), public space, and language use that is inclusive, informed, and respectful (GLHV, 2009; National LGBTI Health Alliance, 2013), and equally, resistance to this in Australia (Brown et al., 2018) and abroad (Zimman, 2017). With this awakening of a move for social change, as with the same sex marriage debate, a voice of opposition has grown, of transphobia within areas of community. The Safe Schools Program has been one such example of an opportunity which was enabling of safety, growth and respect for diversity, but which also ignited opposition and phobic discourse. This program sought to enable teachers, parents and students within school communities to work with each other to foster respectful relationships of inclusion and safety for all (Victoria State Government, Education and Training, 2018).

The expanse of experiences and needs of people identifying as trans and or gender diverse, and of the wider community within the context of this new social landscape might well be contemplated within a scope of universal experiences of transition, loss, the unknown and of new frontiers, identity expressions and narratives.

This paper will explore some examples of therapeutic issues and opportunity from art therapy practice. A therapeutic approach that attends to and seeks to engage with practice that is decolonising, and person centred emerges as important. Discussion of the role of art therapy process within this focus area gives rise also to consideration for the teaching pedagogy of institutions who nurture our emerging art therapists, the art therapy trainees of today, who situate their learning also within this time of social change. Vignettes will serve to provide material for discussion, and to highlight some of the complexities of this area of social change as it intersects with art therapy practice and process, for clients, therapists, students and teachers alike.

Vignette 1 – Heuristic inquiry

The material in this vignette was first presented at the 2017 Australian and New Zealand Transgender Health Biennial conference.

The role of art making and the art object to support identity and transition became a point of investigation for the author/subject through heuristic inquiry and theme-based analysis during their own process of accessing services to support aspects of transition. Arising from this study were themes that supported self knowing, clarity, and the importance of time.

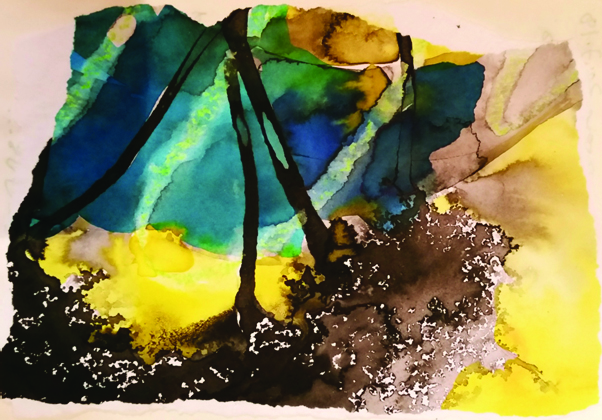

The requirement to attend at least three sessions with a psychiatrist in Australia to obtain a letter allowing for gender affirming surgery has been viewed at times, historically and anecdotally within the trans community, as frustrating or oppressive, with experiences of resentment, (Green, 2000) and intrusiveness (Brown & Rounsley, 2003). Further, the requirement has been seen as an unnecessary process that can be time consuming and humiliating (Reid, 1998) and even as “an adversarial encounter” (Newman, 2000, p.399). Surgery is only one aspect of transition, or gender affirmation, and is not chosen or accessed by all people who identify as a gender other than that assigned at birth. For many people, accessing the services of a psychiatrist still connects to a deficit, to something being wrong, and to a perceived power imbalance between doctor and patient (Speer & Parsons, 2006). The question of body sovereignty arises here. In this study, an experience of value for this required process, a new narrative, through the identification of aspects that were important to the subject within this contemporary consultation space were located through time. Art making was central to supporting this engagement with time, which provided the opportunity for extensive reflection, and for lived experience of and with the questions posed within the psychiatric consultations. Art making supported mental preparation, and enabled an internalising of respect and recognition of validity of self. The informed, safe and respectful space provided by the consultant was experienced initially as an island – the only place of safety, recognition and respite within a social context that is still voicing phobia, and a lack of inclusion. Through exploring elements of what created this space a heuristic process of art making enabled the subject to internalise this concept independently. Using a space in the vicinity of the consulting rooms, a fountain and pond in the grounds of a nearby church, (Figure 1) the subject was able to locate symbolism, and experience an environment that enabled reflection and internalisation of the space of the therapeutic service. Art making to explore the site, much as one might do in a university fine arts program (Figures 2–5), fostered an agency of self.

FIGURE 1 | Reflective space – Church grounds. Pen and watercolour on paper. Ange Morgan 2016

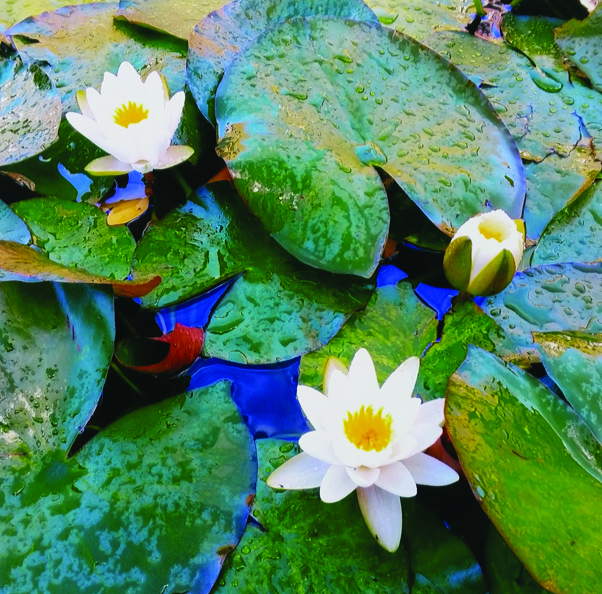

FIGURE 2 | Exploring place – Lily pond. Photograph. Ange Morgan, 2016

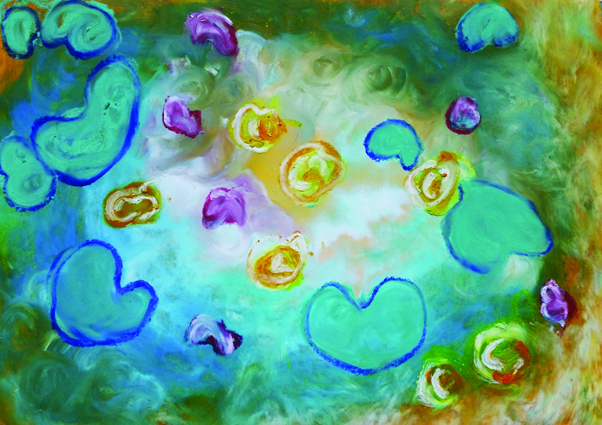

FIGURE 3 | Exploring place – Lily pond. Oil pastel on paper. Ange Morgan, 2016

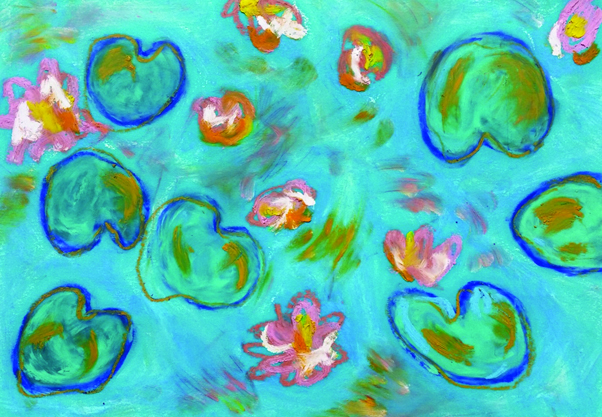

FIGURE 4 | Exploring place – Lily pond. Oil pastel on paper. Ange Morgan, 2016

FIGURE 5 | Exploring place – Crow. Photograph. Ange Morgan, 2016

The image of the group of bison (Figure 6) emerged out of a growing art making practice, initially of no more significance than as a photographic image to engage in drawing practice with. Its symbolism of belonging, which emerged through the process of engaging with the psychiatric sessions, began to serve as a reference to prepare for and weather the challenges of navigating a new landscape which included isolation and transphobia. The message of the image – of the human need to belong, affirmed any challenge that came when there was no place to land. It became a collection of knowing.

FIGURE 6 | Bison. Graphite and chalk on paper. Ange Morgan, 2017

Vignette 2 – A weekly art therapy group for adult day patients in a mental health service

This weekly group for adults experiencing a range of mental health challenges is informed by psychodynamic and art-based/Open Studio approaches to group therapy, within a recovery framework. The group has also drawn on narrative, phenomenological and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) approaches at times. For this group of approximately ten adults, it was considered that due to the hospital responding to recognise the therapist’s transition and affirmed, non-binary identity, clients of the service needed to be informed of the correct pronoun use for the therapist, so that there would be no confusion during administrative, assessment, and other therapeutic service contact with the wider staff body that clients may interact with. The introduction of new/different pronouns for the therapist, to be used by clients and staff meant that some brief disclosure to clients in the day group was required. The introduction to this news grew out of the term already used as a collective, non-binary pronoun (folks) for the group, and of which group members had commented on in recent times. Interest had been expressed in the therapist’s use of this term, and the group had discussed and explored the notion of not labelling or presuming a group’s collective or individual gender identities. Themes of inclusion, of otherness, of individual experiences of identity emerged which had previously been invisible or unexplored by the group. One group member shared their Aboriginal identity, background and experience of self; a temporary resident with uncertain visa status from another culture and place shared the experience of existing in an uncertain space, between cultures, with ties to both. We explored identity broadly, and shared this further through art making. Pride emerged, of Aboriginal identity, of identity connected to sexuality, of migrant identity. Materials such as the bark of the Melaleuca tree, otherwise known as paperbark were gathered and turned into an important piece of work for the young person of Aboriginal descent. Colour was used through art making to explore culture. One group member became a focus of interest and support through inquiry by others into the rich layers of what it means to be a young Australian of Southern European descent today.

With this background in group process, the news that the art therapist had taken the decision to engage in a process of transition in the workplace and identified as non-binary resulted in a continuation of this discussion. Initially some group members needed clarification of what the terms meant, and how to use pronouns they and them. Themes of power vs. equality in the healthcare system became a focus in discussion. Group member’s relationships with their other treating professionals became a focus, and therapeutic work was explored broadly. A sense of sadness and loss was expressed, via the focus on one group member’s church splitting due to disagreement over how to handle same sex marriage.

And in the following weeks, further emerging themes of grief and loss, the therapist as human, and as a pedestal that had fallen also surfaced. It is suggested that a central emerging exploration from this news was that of self in relation to other, and this included self in relation to the group. Role, Dynamic and Intimacy vs. Isolation rose up in the art making and psychodynamic space. One young person, who had struggled to share verbally in group or with the therapist, opened up and was able to report relief after sharing aspects of experience that had held deep shame. Throughout this process we shared the experience of art making together, with a strong focus on observing our processes, and how these served us. We worked with scribble (Figure 7), with hard and soft materials, with ripping and tearing (Figure 8), with abstraction (Figure 9) and reproduction (Figure 10). Freedom vs. feeling held by a directive became a focus, and role in relation to the directive was also explored: “I wanted to rebel against the task, but it’s so difficult for me to do this” from one group member became a valued discussion about refusal and authenticity, and again, role in relation to others in this space.

FIGURE 7 | Scribble work in studio art therapy – Making work with clients. Pen and watercolour on paper. Ange Morgan, 2018

FIGURE 8 | Tearing and collage work in studio art therapy – Making work with clients. Mixed media on paper. Ange Morgan, 2018

Figure 9 | Abstraction work in studio art therapy – Making work with clients. Ink and watercolour on paper. Ange Morgan, 2018

FIGURE 10 | Figurative work in studio art therapy – Making work with clients. Ink, watercolour, wax and pen on paper. Ange Morgan, 2018

The group journey that developed from this initial response traversed many landscapes:

Clients located movement within their therapeutic journeys, such as exploring other relationships in their lives, recognising experiences of loss, anxiety around change, and their own experiences of oppression. The interpersonal work of the group was illuminated as members began to share themselves with each other as they explored their responses to the identity of the therapist. Personal identity became a focus for many, and a sense of shared “otherness” was celebrated as group members revisited their understandings of what is valued in their weekly art therapy space: “we feel understood by each other without having to explain; that we don’t feel judged; we feel less alone as we experience others also working with similar challenges in the world. We all need a place to belong.”

Vignette 3:Art studio group in a drop-in centre for people experiencing homelessness

In a community drop-in setting providing a range of services including art therapy to people experiencing homelessness, a group of men meet for a weekly art studio group. The large charity organisation providing these services has engaged in consultation and development of a restructured intake process and range of services to respond to the needs of clients from the gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender/transsexual and intersex (GLBTI) community. One aspect of this process has been inclusive language on intake forms.

Why do they need me gender on this form? From amongst the circle of men around the art table, this question arises. We have all gathered together, a volunteer university art student, the art therapist/author and several clients of a homelessness service to work with art materials and share the studio space. As is so often the case in such a setting universally, the art begins to enable connection and discussion (Fry, 2005; Golub et al., 1993; Swainson, 1990; Timm-Bottos, 2006). The question posed is an important one. Clients have a right to know why a service or organisation gathers their information.

As the group worked with art materials in their own individual ways, we were able to respond to, discuss, and explore this question together. The group showed an initial confusion between sexuality and gender. But as we discussed the differences together, and our work continued to unfold, a diversity of gender identity and sexuality began to emerge, and a dynamic of inclusion and tolerance prevailed. In this drop-in centre space, within the process of art making that is studio based, self-directed, and ever changing in its group membership, one man found it safe enough to disclose to the group of others his experience of Biphobia which he had encountered for most of his adult life. The group located more that was shared in their differences, than was not. Here we might consider the capacity of one experience of otherness, marginalisation and oppression to be able to include and care for another. Themes arose of respect, inclusion and rights, across a broad range of experiences. Art making continued around the shared table, and the dynamic of support and inclusion between group members was evidenced in their listening, sharing, joking, and continued presence.

We all need a place to belong.

Hiscox noted in regard to the education of art therapy trainees in America that to fail to acknowledge persons of colour as having a range of experiences that are different from the dominant White population, often identified as colour blindness, is to engage in racism, and is to fail to meet students with the training that will assist them to work in the field (1998). Similarly, a blindness to or denial of difference or issue in regard to TGD persons is problematic, and ignores the daily challenges and oppression that influence identity, lived experience, and health for this community who fall outside of mainstream social structures.

Hogan suggests that gender is central to our understanding of self identity, and that therapists must be able to engage in exploration of matters of gender and identity that are free from imposed or generalised norms (2002). Hogan’s example of the gendering of children from birth in a binary way, as she found with her baby on a bus trip: “is that a boy or a girl?” is echoed in art therapy literature with the frequent use of her or him/he or she. To lean into our social conditioning regarding gender norms is to examine our own frameworks for understanding ourselves and our clients, as Hogan (2002) calls for, and in doing so, to support students: through examination of education pedagogy; and in the classroom to challenge these notions as they present.

On review of the practice vignettes, art making as a place to connect with the art process reemerges as fostering growth and change, no matter the theme or subject matter at hand, allowing us to connect, and belong to ourselves, and with others, in place and through time.

About the Author

Ange Morgan is a registered art therapist, working with adult and child populations in mental health, homelessness, and family violence, within public, private and community settings. Additionally Ange lectures and provides supervision in the Master’s of Art Therapy program at La Trobe University. Previously, Ange completed a BA (Dance Performance) at VCA/Melbourne University, and a BA (Hons) in painting at RMIT. In exploring the experience of transition and the therapeutic space which assists this process, Ange has drawn on their backgrounds in art making and art therapy practice and research to understand their lived experience.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Australian Healthcare Associates (2018). Trans and Gender Diverse Service System Development Project. Future development of health and support services for trans and gender diverse Victorians: Key directions paper. Victorian Department of Health and Human Services https://www.ahaconsulting.com.au/wpcontent/uploads/2018/03/TGD-Discussion-paper.pdf

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2017). 1800.0 – Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey, 2017. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/1800.0

Brown, C., O’Leary, J., Trau, R. & Legg, A. (2018). Out at Work, from Pride to Prejudice . Diversity Council Australia. https://www.dca.org.au/research/project/out-work-prejudice-pride.

Brown, M. & Rounsley, C. (2003). True selves: Understanding Transsexualism for Families, Friends, Co-workers and Helping Professionals. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Fry, H. (2005). Self, environment and others. Parity 18(9): 6–7.

GLHV (2009). Well Proud – A Guide to Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Inclusive Practice for Health and Human Services. Melbourne: Department of Health, Victorian Government.https://www.glhv.org.au/health-service-audit/well-proud-guide-glbti-inclusive-practice-health-and-human-services.

Golub, W., Nardacci, D., Frohock, J.A. & Friedman, S. (1993). Interdisciplinary strategies for engagement and rehabilitation. In S.E. Katz , D. Nardacci and A. Sabatini (eds). Intensive Treatment of the Homeless Mentally ill . Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Green, R. (2000). Gender identity disorder in adults. In M. Gelder , J. Lopez-Ibor and N. Andreasen (eds). The Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hiscox, A. (1998). Cultural diversity and implications for art therapy pedagogy. In A. Hiscox and A. Calisch , (eds). Tapestry of Cultural Issues in Art Therapy . London; Philadelphia, PA: J. Kingsley. pp. 276–288.

Hogan, S. (2002a). Contesting identities. In S. Hogan (ed) Gender Issues in Art Therapy . London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. pp. 11–30.

Telfer M Tollit M & Feldman D. (2015). Transformation of health-care and legal systems for the transgender population: the need for change in Australia. Journal of Paediatric Child Health ; 51: 1051–1053.

National LGBTI Health Alliance(2013). Inclusive Language Guide: Respecting People of Intersex, Trans and Gender Diverse Experience. http://lgbtihealth.org.au/inclusivelanguage/

Newman, L.K. (2000). Transgender issues. In J. Ussher (ed). Women’s Health: Contemporary International Perspectives. Leicester: BPS Books

Reid, R. (1998). NHS v Private Treatment for Transsexuals . The Fifth International Gender Dysphoria Conference, Manchester England. London: Gendys Conferences.

Riggs, D.W. & Due, C. (2013). Gender Identity Australia: The Healthcare Experiences of People Whose Gender Identity Differs from that Expected of Their Natal Assigned Sex. Flinders University. https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/21_Pub_Sub_Melody%20Moore_Transhealth_Flinders_University_Gender_Identity_Australia_Report.pdf

Speer, S.A. & Parsons, C. (2006). Gatekeeping gender: Some features of the use of the hypothetical questions in the psychiatric assessment of transsexual patients. Discourse and Society, 17 (6).

Swainson, C. (1990). Art therapy and homeless people. In M. Leibmann (ed). Art Therapy in practice. London and Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Timm-Bottos, J.. (2006). Constructing creative communities: reviving health and justice through community arts. Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal 19(2): 12–26.

Victoria State Government, Department of Health (2018). Health of Trans and Gender Diverse People: Key Messages. Melbourne: Department of Health, Victorian Government. https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/populations/lgbti-health/rainbow-equality/lgbti-populations/trans-and-gender-diverse-people-health.

Victoria State Government, Education and Training (2018). Department program: Safe Schools. Melbourne: Department of Health, Victorian Government. https://www.education.vic.gov.au/about/programs/Pages/safeschools.aspx?Redirect=2.

Zimman, L. (2017). Transgender language reform: Some challenges and strategies for promoting trans-affirming, gender-inclusive language. Journal of Language and Discrimination 1(1): 84–105. http://www.lalzimman.com/papers/Zimman2017TransgenderLanguageReform.pdf