FIGURE 1

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2018) 4(1):66–77 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2018/4/7 |

Reflections on Minority Cultures in China: A Photo Essay

对中国少数民族文化的反思:一篇摄影短文

New York University Steinhardt, USA

Abstract

This article describes a journey by the author to China where he documents in words and photographs the lives of people from minority cultures, especially the Miao and the Dong. In further in reflecting on the journey, the author acknowledges the impact of his mentor – a refuge from mainland China in 1949 – and his own heritage as an American Jew descended from generations of East European Jews displaced by pograms and by the Holocaust.

Keywords: Drama therapy, Culture, Minority, Jewish, Muslim, Miao, Dong

摘要

本文描述了作者到中国的旅程。他用文字和照片记录了少数民族文化中人们的生活,特别是苗族和侗族。 此外,在回顾旅程时,作者承认他的导师-1949年来自中国大陆的难民以及他自己作为美国犹太人的后代所产生的影响,源于几代东欧反犹骚乱和大屠杀。

关键词: 戏剧治疗, 文化, 少数民族, 犹太人, 穆斯林, 苗族, 侗族

Some years ago, I served as an outside reader for a doctoral dissertation on Chinese art and aesthetics at NYU. I knew the doctoral student only through her dissertation and her address on the cover page which was the same small Hudson River town where I lived. She lived in China and came to New York to study art for her doctoral degree. When we met at her final oral exam I noted the coincidence of our common addresses.

‘I am nervous,’ she told me. Knowing I was a therapist, she asked, ‘Do you have any suggestions to calm myself down before the exam?’

‘How about tai chi?’ I joked, aware of my spurious assumption that all Chinese people practiced tai chi. I might have expected her to respond, ‘Do you play football?’

She did not – as she was more respectful than I. But she did tell me that she lived temporarily with her Chinese uncle Professor Wu who, among other things, was a tai chi master.

‘He came to New York in 1949 – just before the revolution – to study for his doctorate and never returned because his father was a general in Chiang Kai-shek’s army.’

‘Funny, because I’ve been feeling anxious lately and actively searching for a tai chi teacher.’

‘I will introduce you,’ she said, less anxious than before.

She passed her oral exam with distinction and I met Professor Wu the following Sunday. Over several years he became not only my tai chi master but also my guide into Chinese philosophy, religion, literature, cooking, culture and geography. He helped me prepare intellectually for my several trips to explore Chinese culture beginning in the mid 1990s.

For the past 10 years I have been an occasional lecturer and workshop leader at the Shanghai Theatre Academy (STA), introducing drama therapy to mostly students and professionals of theater and education. Two years ago my son Mackey became a student at STA which I visited as often as possible and each time we took a journey into regions known for their ethnic minorities. The term ‘ethnic minority’ is problematic because it refers only to non-Han majority Chinese living within the People’s Republic of China who are officially recognized by the Chinese government. Groups who identify as Jewish and Tuvan (among others) are not recognized as ethnic minorities. Being Jewish ourselves, we decided in 2016 to first visit Kaifeng – the ancient Song Dynasty capital of China and historical home of diasporic Jewish wanderers who travelled the ancient silk road into central China. There were only a handful of Jews left in the city – between 400-500 – all of whom had inter-married with Han Chinese people over many generations. Most of the Jews of Kaifeng are hardly aware of their roots. And because the government has prohibited the practice of Jewish rituals, those who still embrace their faith do so largely underground. We did manage, however, to meet a bold woman with Jewish ancestry who took us to her apartment and showed us a few of her remaining family photographs and religious items. We were aware that she risked tangling with the authorities if they knew she was meeting with foreigners. Everything she had was frail and faded – all under plastic wrapping.

Mackey and I posed for a photo with our guide (see Figure 1) who shall remain anonymous. We stood in front of a flag of the state of Israel. In the background was a poster of the old Kaifeng Temple destroyed by the Chinese government and marked by the name of a website www.chinesejew.org which presently is not operative. Old family photographs lined the rear walls.

FIGURE 1

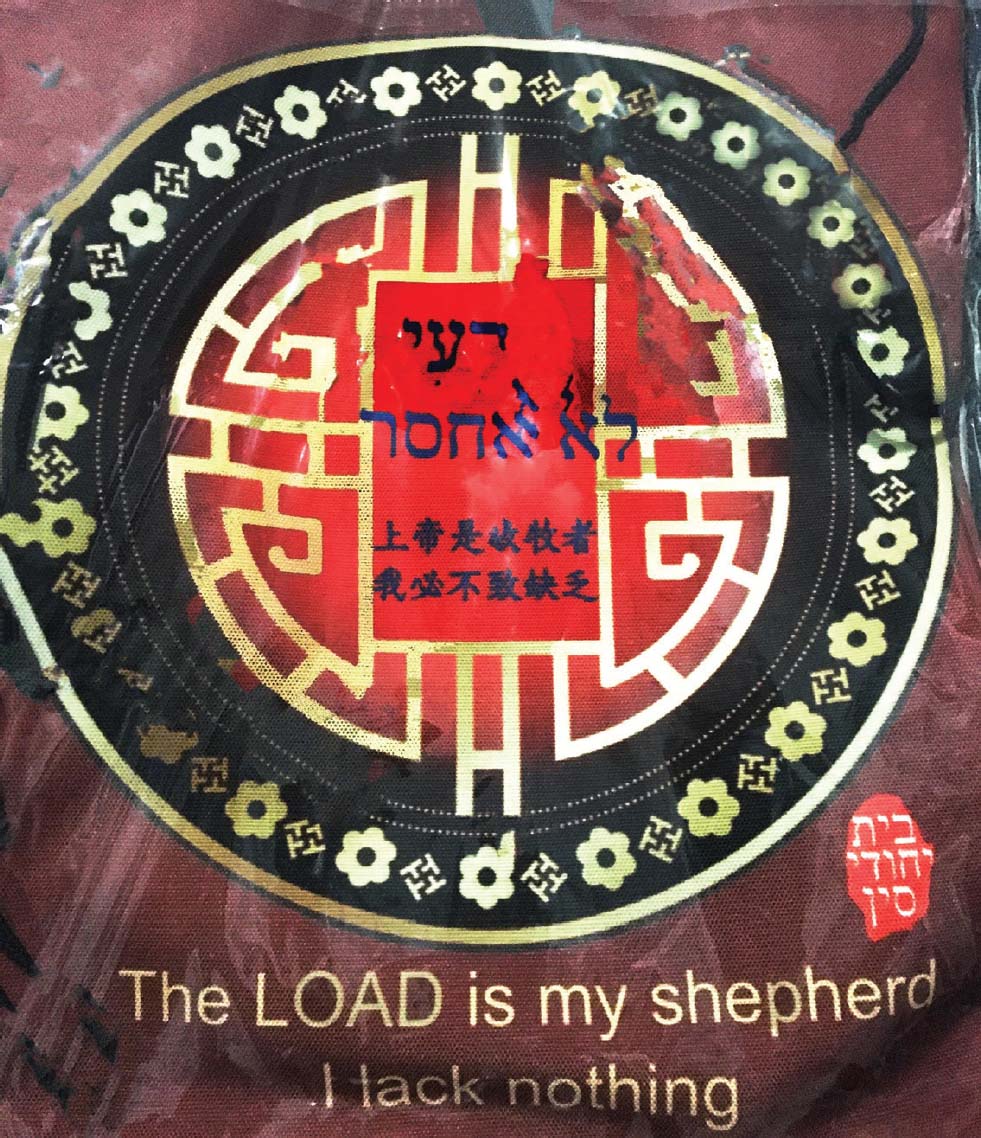

In Figure 2 we see – in close-up – a mix of Chinese and Jewish cultural imagery and calligraphy. The beginning words of the Lord’s prayer appear in an odd, comical English translation – ‘The LOAD is my shepherd.’ I noted that the weight of being a minority – especially a forbidden one – was indeed a heavy load and required an intrepid shepherd as a guide.

FIGURE 2

The night we arrived in Kaifeng train station was very smoggy and the feeling in the plaza outside the station was surreal. A large, brightly colored, childlike statue stood prominently in the plaza (see Figure 3). It was January and many of the city workers were beginning their preparations for the lunar new year festivities.

FIGURE 3

The next morning we explored Kaifeng in all its glory. Its traditional buildings and pagodas were magnificent (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 4

Since our interest was in ethnic minorities, we wandered to the Muslim district. A group of men were frying lamb outdoors in a massive metal pot – food to be served to families and in restaurants in the district. They were very friendly and invited us to watch their preparations and to sample the food. (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5

While in Kaifeng, I was particularly attracted to the people who carried out the daily tasks of city life – such as the parking lot attendant in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6

From Kaifeng we flew to Guizhou Province in southwestern China. This is an area which – which though poor and undeveloped – is known for its diversity of ethnic minorities. We visited villages of two such ethnic minorities – the Miao and the Dong – who live in the Qiandongnan Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture. Following are several examples of life in a Miao Village.

FIGURE 7 | Entrance to an Old Walled Village

FIGURE 8 | Miao Man with Flute

My experience in a very old Dong Village was equally powerful – as if I was transported to village life as it existed centuries ago.

FIGURE 9 | Women selling produce at Market.

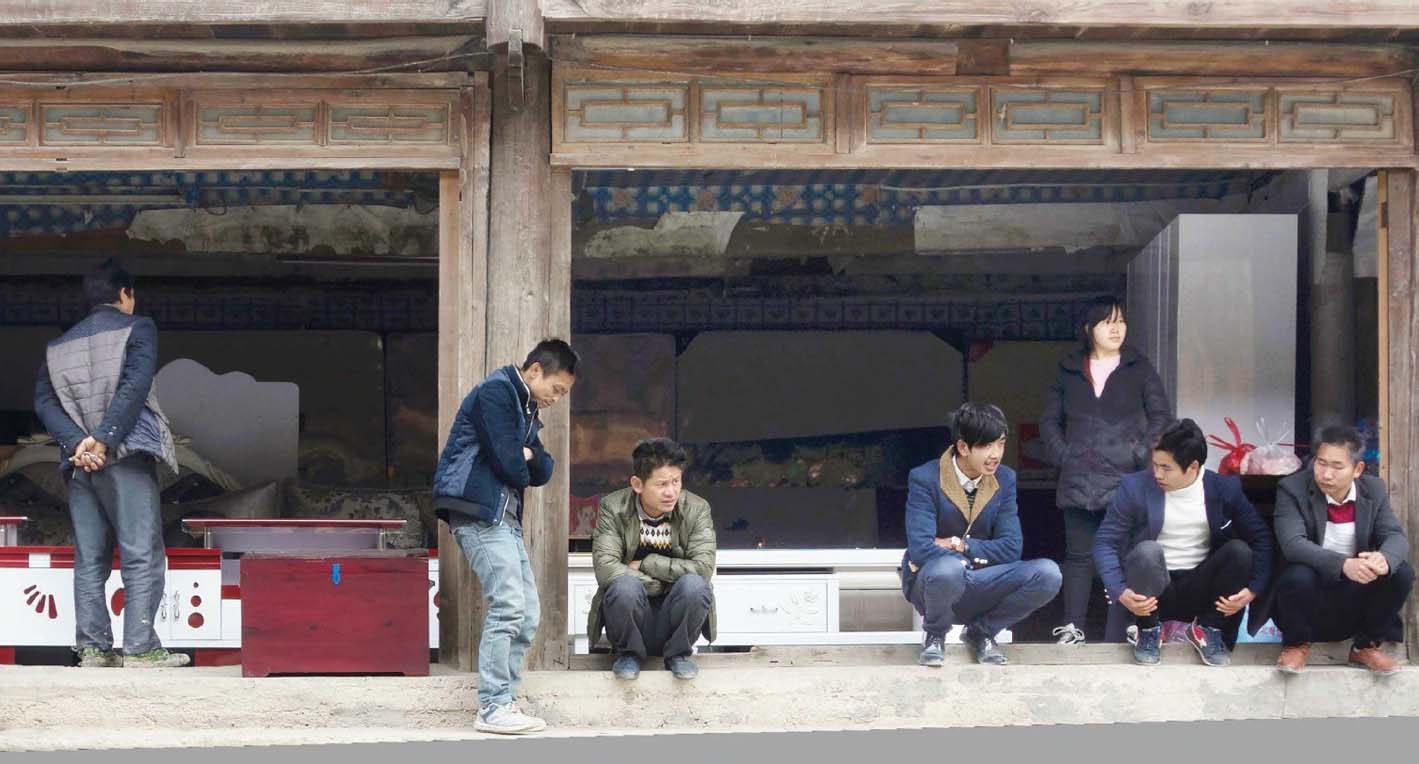

FIGURE 10 | Young people near the Square

FIGURE 11 | Cutting meat in the Square

FIGURE 12 | An Old Temple

FIGURE 13 | Family Homes

We returned from the mountains of Guizhou with a reassuring sense that – despite the rapid industrialization, technological and political transformations in China – traditional cultures were still intact. As we were leaving, we stopped at a tiny tea house for a drink. While there, I heard the cry of a child behind me. When the child’s cry subsided, I turned around to see that the mother had placated the child by giving it a cell phone (see Figure 14). Such a moment of seeing a toddler in a traditional village playing adeptly with the technology that defined the new China provided the transition I needed to re-enter the bustle of Shanghai (see Figure 15).

FIGURE 14

FIGURE 15

In a final transition, I waited at the airport for my flight to New York. There I watched a young woman eat a bowl of noodles (Figure 16) and thought of how I would soon be walking the streets of Chinatown in my city with its mix of every conceivable culture on the face of the earth.

FIGURE 16

On the plane, I thought about Professor Wu who had passed some years before; I thought of how he left home as a young student, never to return for political reasons, and how he recreated his old cultural traditions in our small Hudson river town. I thought of how he helped me find my way into an ancient culture that is now fading fast. At that moment I had a question to ask him and so I did. ‘Professor Wu, did you ever want to return to China? And if so, why didn’t you go?’

In my mind, he answered simply as he always did. ‘It is not possible to return. Everything changes. I can only build what I know and love in the present – wherever I am.’

And as I came home, a relative of wandering Jews – of generations who, in the old country, experienced pograms and then the Holocaust – I committed to doing just that; to building what I know and love in my home. I travelled to China to complete this dialogue with Professor Wu that reached back into ancient Chinese dynasties and raced forward to a small Hudson River town a stone’s throw from New York City – my hometown.

About the author

Robert J. Landy, Ph.D., RDT-BCT, LCAT, Professor Emeritus, New York University, Founding Director, Drama Therapy Program