FIGURE 1

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2018) 4(2):199–205 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2018/4/30 |

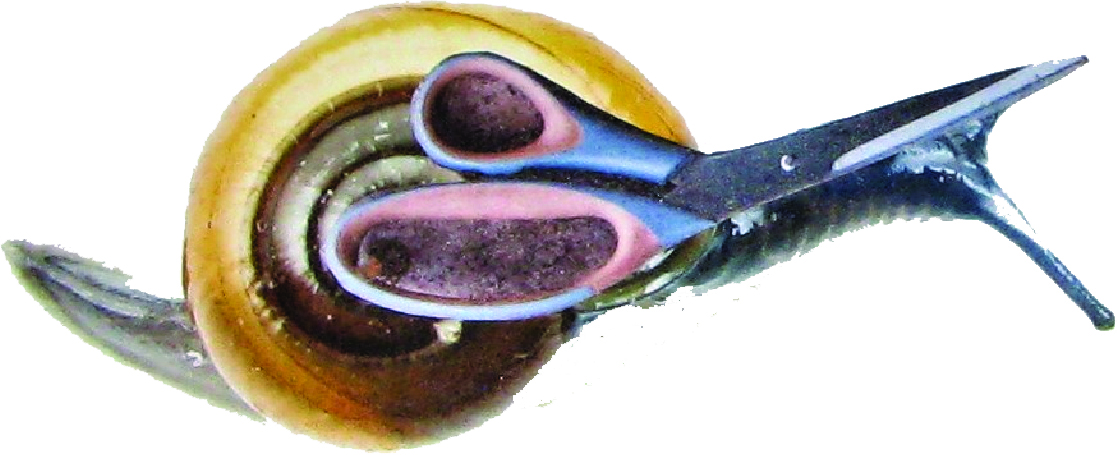

Lips and Scissors

Whitecliffe College, New Zealand

FIGURE 1

i

tasting arts-based research and auto-ethnography

means tasting with my whole body

it means tasting my home, my world, my self

with the sensitive sled1

of my flesh2

it means closing my eyes

and feeling the path in the dark

krishnamurti said

when we teach a child the name for bird

the child will never

see a bird again3

I hope to lose my words for a moment

to be open enough

and soft enough

and lost enough4

that I might feel

the feathery pulse

on my finger:

the exquisite lightness

of being5

FIGURE 2

ii

as I taste

I snip

my slick and slippery

lips move like a pair of scissors6

leaving a trail of meaning

how can I avoid

cutting my own tongue?7

FIGURE 3

iii

who is guiding my scissors?

who’s voice is whispering in my ear?

what parasitic prejudice?

what privilege?

what hope?8

when the skin on my back

is awake

I can feel the hands, the claws

that guide me from behind

they lift their faces

and look towards the light9

FIGURE 4

iv

it is necessary

to kiss the toad

or at least

lick its eyelid,

to look it in the eye

or at least

sit beside it10

the performance of my particular11

tongue and toad

might move you

or disgust you

how much of my toad

do you need to see?

and which part of my

tongue?

FIGURE 5

v

multiplicity and

proliferation

are heavy

words to digest

how many birds

is too many

birds in the nest?12

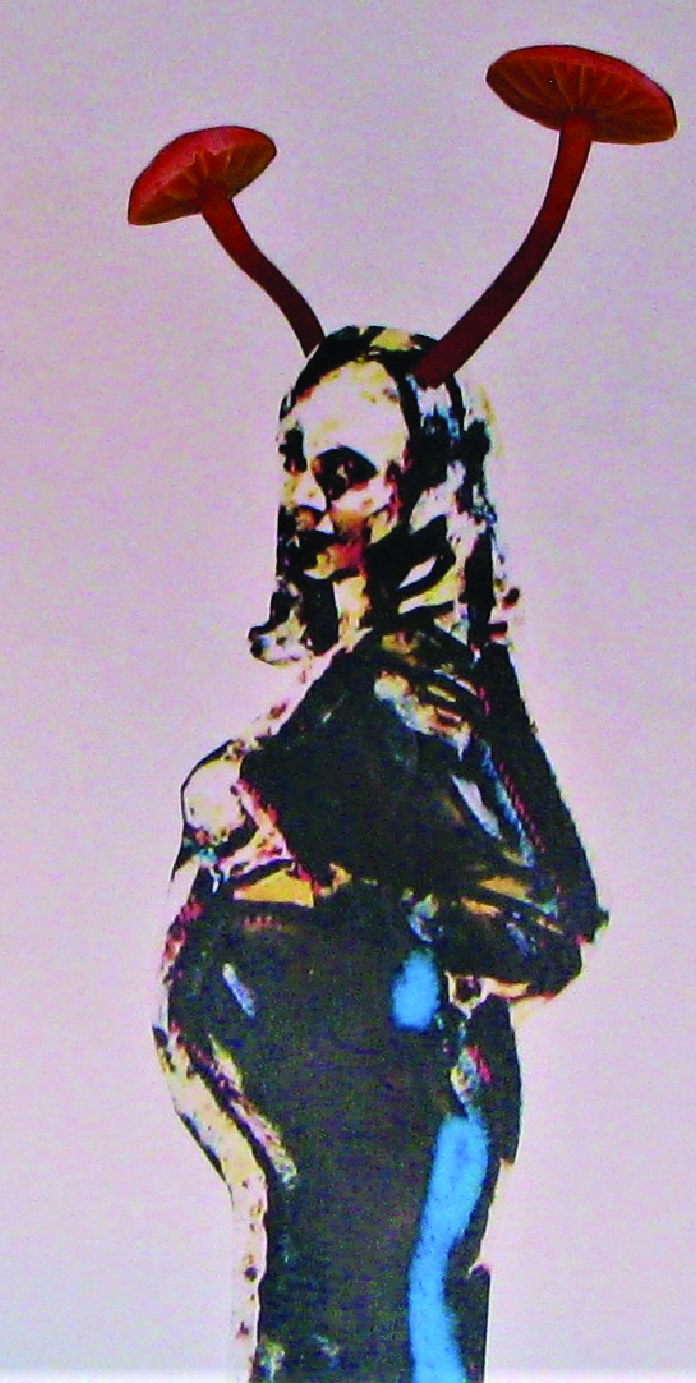

FIGURE 6

vi

do I need to explain my metaphors?

and trace their source? and how?

can I just let them bloom between us?13

look here!

above thousands of kilometres

of mycelium running

and digesting the underworld14

my art is rising

like the fragile face

of a mushroom

FIGURE 7

About the Author

Rata Gordon is a poet and creative facilitator living on Waiheke Island, New Zealand. She is currently studying towards a Master of Art Therapy at Whitecliffe College. Rata’s poems have been published widely including in Best New Zealand Poems. Her first poetry collection Thumb and Tongue is forthcoming with Victoria University Press. www.ratagordon.com

1“The snails on the pink sleds of their bodies are moving / among the morning glories” is a line of poetry by Mary Oliver (1992).

2Arts-based research emphasises embodied knowledge (Kapitan, 2018; Leavy, 2017)

3Jiddu Krishnamurti, as referred to by Adyashanti (2011, p. 6-7).

4Eberhart and Atkins suggest that in expressive arts therapy we focus on poiesis: “knowing by creating,” in contrast to theoria: “knowing by reason,” (p. 44) which involves suspending our habitual reliance on language (p. 86). McNiff (1998) says that the ABR “should correspond as closely as possible to the experience of therapy” (1998, p. 170).

5The Unbearable Lightness of Being is a book of philosophical fiction by Milan Kundera (1984).

6“Lips moving like a pair of scissors” is a line from Kate Atkinson’s (1995) novel Behind the Scenes at the Museum (p. 324).

7Varney et. al. (2014) highlight the tension between authenticity and being taken seriously by ones audience when conducting ABR.

8Auto-ethnographic research requires a rigorous examination of ones own context (Gray, 2011), which can be challenging because one is ‘inside’ oneself.

9Fortunately, arts-based processes can support the surfacing of ‘shadow’ aspects of self, making what was invisible visible.

10ABR is performative: it does not “simply describe or represent things [...] it actually does things” (Kapitan, 2018, p. 217).

11ABR focuses on the particular, unlike many other research methods that seek generalisations (Kapitan, 2018).

12A challenge of ABR is that it can create masses of data and multiple viewpoints (Kapitan, 2018), which can become hard to grapple with.

13McNiff (2014) advocates for allowing art to “speak for itself”.

14Mycelium Running is a book by Paul Stamets (2005). Mycelium is the part of a fungus which lives underground and absorbs nutrients. It is made of microscopically thin threads that can spread for thousands of acres and are thought to be the largest living organisms in the world (Stamets, 2005).

References

Adyashanti (2011). Falling into grace: insights on the end of suffering. Boulder, CO: Sounds True.

Atkinson, K. (1995). Behind the scenes at the museum. UK: Doubleday.

Chilton, G. & Scotti, V. (2014). Snipping, Gluing, Writing: The Properties of Collage as an Arts-Based Research Practice in Art Therapy. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 314 pp. 163–163.

Gray, B. (2011). Auto-ethnography and arts therapy: The arts meet healing. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Arts Therapy 61. pp 67–67.

Kundera, M. (1984). The unbearable lightness of being. France: Gallimard.

Leavy, P. (2017). Research Design: Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, Arts-Based, and Community-Based Research Approaches. New York: The Guilford Press.

Marttila, A. (2018). Cats on Catnip. NY: Running Press Adult.

McNiff, S. (1998). Art-based research. Boston, NY: Shambhala.

McNiff, S. (2014). Art Speaking for Itself: Evidence that Inspires and Convinces. Journal of Applied Arts & Health 52. pp 255–255. doi: 10.1386/jaah.5.2.255_l

Oliver, M. (1992). New and Selected Poems, Vol. 1. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Stamets, P. (2005). Mycelium running: how mushrooms can help save the world. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press.

Varney, H., Rumbold, B., and Sampson, A. (2014). Evidence in a Different Form: the Search Conference Process. Journal of Applied Arts and Health 5 (2). pp 169-178. doi: io.i386/jaah.5.2.i69_i