Special edition: Outsider Art in China (3)

This is a special edition featuring an interview with Guo Haipin, the pioneer and leading figure of outsider art in China. The edition is introduced by Shaun McNiff and it includes a response by Daniel Wojcik, author of Outsider Art: Visionary Worlds and Trauma.

- Creating Lives through Art – An Introduction to Outsider Art in China with Reflections on Outsider Art: Visionary Worlds and Trauma by Daniel Wojcik. By Shaun McNiff

- Outsider Art in China — An Interview with Guo Haiping. By Chen Shushan

- A Dialogue with Daniel Wojcik on “Grassroots” Artistic Expression and Its Redemptive Power. By Shaun McNiff

A Dialogue with Daniel Wojcik on “Grassroots” Artistic Expression and Its Redemptive Power

与 Daniel Wojcik 就“草根”艺术表现及其救赎能力的对话

Shaun McNiff, Lesley University, USA

Shaun McNiff: Can you tell our readers how you developed your interest in what we call outsider visual art?

Daniel Wojcik: I think my interest in what has been called outsider art/art brut/vernacular/self-taught art goes back to my experiences as a child – my parents took me to roadside attractions, dinosaur parks, underground gardens and other interesting and unusual locations. These were fascinating places of uninhibited and free-form creativity for me. For instance, I remember being amazed by Sabato Rodia’s enormous shimmering towers in Watts that he built by himself over a thirty-year period (Figure 2), and then later seeing Tressa Prisbrey’s glowing bottle village in Simi Valley. She actually was there – giving tours to visitors for 25 cents or something like that – and I wandered through her hand-built structures. This made an impression on me (Figure 3).

FIGURE 1, Cover image of Outsider Art by Daniel Wojcik.

FIGURE 2-1, 2-2, 2-3 Sabato Rodia’s towers and mosaic work on the south exterior wall and interior of his structures. Photograph Daniel Wojcik.

FIGURE 3-1, Tressa Prisbrey with her collection of dolls at Bottle Village, Simi Valley, California.

FIGURE 3-2, Mosaic tile walk way and the Rumpus Room house at Tressa Prisbrey’s Bottle Village, Simi Valley, California.

When I was travelling through Europe as a student in the late 1970s, I haphazardly visited the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland in an unplanned detour. I was completely floored by what I saw – the remarkable and unbridled creativity of individuals who had no formal artistic training was unlike anything I had seen before. I had been visiting many art museums throughout Europe but there was something transformative about the raw power of art brut in Lausanne; it was shocking and almost indescribable, with a startling originality and an uncanny strangeness that was somehow weirdly familiar. And then, even more, I was struck by the tremendous ingenuity of many of the artists who often created with no resources – salvaging materials and creating in response to trauma or adverse circumstances. I was deeply moved and enthralled with their art. I could not get what I saw out of my mind and wanted to know more.

Over the years, whenever possible, I began to visit “outsider” art environments. I met many self-taught artists and my talking to them and attempting to understand their reasons for making things became a primary interest for me – perhaps the most important and rewarding thing. Howard Finster’s work (Figure 4), Tyree Guyton’s street art Heidelberg Project in Detroit, and then my friendship with Ionel Talpazan, a refugee from Romania who was selling his art on the streets of Manhattan were important (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4, Howard Finster, A Feeling of Darkness, 1982. Tractor enamel on wood, 21 x 34 in. (52.7 x 86.4 cm). Photograph Jim Prinz. Courtesy of the Arient Family Collection.

FIGURE 5-1, Ionel Talpazan, Future UFOs Diverse Diagrame: 22 Modele Advanced Exstra Terestriale Tecnologÿ for Planeta Earth, 2000. Oil crayon, marker, pencil, and ink on paper; 30 x 40 in. (76.2 x 101.6 cm). Photograph Daniel Wojcik.

FIGURE 5-2, Ionel Talpazan, Untitled (Mandala Shape Flying Saucer/Special Design, Secret Theory–Technology), 2003. Oil crayon, marker, poster paint, pencil, and ink on paper, 30 x 53 in. (76.2 x 134.6 cm). Photograph Daniel Wojcik.

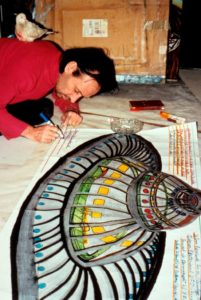

FIGURE 5-3 Ionel Talpazan works on his Silver UFO drawing, with his dove Maria perched on his shoulder. February, 2000. Photograph Daniel Wojcik.

Later, I discovered the writings of Hans Prinzhorn and others. I also read descriptions of some of the artists I had met, much of which seemed fictionalized at times or written in sensationalistic ways by collectors, dealers, and others. Such depictions bothered me, so I decided that I would try to write a book that attempted to honestly understand these artists and the context for their art; it would try to give them voice so they could speak about their art in their own words, when possible.

SM: It is intriguing and unique how you apply your background in literature and folklore to this domain – which I feel generates a more holistic and interdisciplinary framework for exploring the art, the artists, and the context of the work.

DW: My MA and PhD degrees are in Folklore Studies (and Mythology) from UCLA, and the program there emphasized an interdisciplinary approach combining literary and cultural studies and drawing upon aspects of a wide range of other disciplines. The Folklore Program at UCLA was attractive precisely because of the holistic perspectives offered and its ethical and street-level approach to understanding forms of grassroots culture and behavior that are often ignored. That helped me tremendously.

In retrospect, I realize that I have always been interested primarily in the artistic process, the human imagination, the ways that people understand the mystery of existence, and the creation of spiritual belief systems. How do people understand the world, deal with adversity, create meaning, and express wonder and enchantment in the midst of pain and suffering? This interest in creativity and the search for meaning led me to folklore studies – or what could be called the vernacular expressive culture of humanity – which focuses on personal and “authentic” (or perhaps even “soulful”) forms of belief and creativity expressed outside of mass media and commercial culture.

SM: Can you give us a sense of how you view the tradition of outsider art scholarship and how you see your work contributing to it?

DW: In my book, I attempt to provide a history of the tradition of outsider art and art brut scholarship. I appreciate the interest in such art as it originated in asylums and later was embraced by certain artists for inspiration. However, as we look back on it decades later, there are also serious problems with how things developed and how individuals were treated. Art brut had a tremendous influence upon modern art – but more important for me was its influence on the field of art therapy. This is something that people acknowledge, but I do not think is recognized enough.

There seem to be certain categories of “scholarship” on outsider art. 1) Books about some collector’s cache of art, usually written by an art dealer, a museum curator, a friend of the family or a promoter of the collection. Such works consist primarily of an overview essay and then short biographies of artists along with images of the collection; these tend to be coffee table books with minimal scholarly value but are nice to look at. 2) Writings that praise and analyze the formalistic qualities of outsider art with little attention to biographical or cultural contexts. These tend to be attempts to legitimate the art and to gain recognition for it in broader art world circles. 3) Writings that highlight biographies of artists but which may emphasize or even exaggerate the artist’s strangeness and disconnection from others and from culture – sometimes in dehumanizing ways. 4) Writings by psychiatrists which attempt to understand the psychological and therapeutic aspects of such art but which often have a diagnostic and clinical perspective that is divorced from cultural contexts and aesthetic aspects. There may be another category I’ve missed…

There has been some fine scholarship in recent years that goes beyond the celebratory, romanticized, or exclusively formalistic approaches to outsider art. In my book I emphasize the behavior and motivations of artists as well as the socio-cultural contexts – a culturally-rich approach very much at odds with formalistic descriptions which tend to be dehumanizing and ignore the personal meanings of such art. I am neither an art critic nor an art dealer. I have nothing to sell. I am interested in human behavior and the artistic process. This means I not only focus on all the personal reasons for creating things, but I attempt to situate individual art-making within local culture, community, ethnic heritage, popular culture and other influences. In one chapter of the book I pay special attention to the religious contexts of such art (e.g., spiritualism, millennialism, Vodou, African American traditions) that often have been neglected.

Although I am not an art therapist, I find some of the writings in that field especially useful – as well as some of the writings of psychiatrists and those in the field of trauma studies. This means I draw upon those influences too in attempting to better understand the relationship between personal experiences, culture, adversity, creativity and the life-enhancing potential of art.

The true intention of my book is to go far beyond an understanding of so-called outsider art; I hope to contribute to a genuine understanding of art and the importance of the creative process in general.

SM: Your book explicitly addresses how the gallery world has not paid enough attention to how these artists always create within a particular community and with a purpose. From my perspective, I think that you also have a vantage point that is fresh and relatively free of all the conceptual bias that tends to permeate the way psychology and the arts therapies have explored the subject and the artists. But as I have said, you make many contributions to these disciplines with your deep and comprehensive focus on the personal, social, and environmental context of the work – all of which ultimately enhances the dignity and humanity of the artists and, in my view, the professional disciplines dealing with these aspects of life.

DW: Well, thank you; you said it better than I could have here! In researching and writing this book, I read everything I could find on the subject – including obscure and rare sources. I also attempted to draw upon the writings of scholars from a range of disciplines. I then tried to distill it all and add my own analysis (based on my interviews and research) and present it all in a jargon-free, inclusive and even-handed manner. I was concerned with the dignity and humanity of the artists as a counter to some previous writings. I was mindful of representing the artists in both a sensitive and an ethical way, adhering to their own perspectives as best as I could.

SM: In relation to what I have said about your book being a seminal text for the arts in therapy, has your work with outsider art given you your own sense of how art heals? Do the artists you study show people everywhere how art heals?

DW: This is a wonderful compliment, coming from you as an internationally known expert on healing and arts therapy. Actually, when I began the project it was not part of my plan or agenda to discuss how art heals; I initially focused on the cultural contexts for the art in order to show that individuals are never completely “outside” of culture. But then as I got deeper into the research, the themes of trauma and adversity and art-making occurred again and again. And then ideas of healing and transformation emerged – not only for individuals but for communities too. This ultimately led to the “art as therapy” part of the book – a realization no doubt obvious for art therapists, but not for me at first.

Yes, art does heal; it is truly life-affirming and it is essential to human existence and well-being. For me, this understanding did not come from reading art therapy books, but from talking to the artists themselves and from reading other accounts and interviews with individuals. I also remembered my own experiences of creating things during times of stress (which I had not even thought about before) and I realized how art helped me too. I had not planned my book to be about how art heals, but I hope that is a main idea that readers take away from it all. The accounts of these self-taught artists experiencing the transformative power of art are inspiring and show us in a concrete way how the artistic process can heal and enrich all of us.

SM: I have always said that art heals through a process of transformation. It draws creative energy from difficulties and affirms life. You appear to agree. This approach to art healing is in sync with what I say in the introductory essay to this featured section of the Journal about how China and East Asian traditions have emphasized “creating oneself as a person through actions that correspond to the transformative forces of nature.”

DW: I agree completely with you here, and your writings on this topic helped me better understand the healing potential of art. What I discovered in my research is that, in some instances, individuals who encounter a life-changing crisis (and who have no background in art) may discover a hidden artistic impulse and realize that the creative process can help them deal with adversity or transform trauma into healing. Some of the people I interviewed said that it was difficult or impossible for them to verbally express traumatic events and related emotions, but through the materialization of memory and metaphor in art they were able to create things that represented experiences and emotions too painful to express in words. These individuals were somehow able to draw upon inner pain and life difficulties as a resource for art-making. As a result they not only created things, but were able to re-create and rebuild themselves in a transformative way. Witnessing the power of art in this context is truly inspiring.

SM: Your book explores outsider art from a global perspective including North America, Europe, and India. Have you had the opportunity to engage with China and East Asia?

DW: I am very interested in outsider art in both China and East Asia, but I have found relatively little published in these areas. I want to learn more. I have heard about international interactions and I know about the important exhibit of Chinese art at the Outsider Art Museum in Amsterdam curated by Guo Haiping and the Dolhuys organization in 2016-2017. But I have not found much else. For my next book on religion and outsider art, and for another project, I am gathering information on artists from Asia and hope to expand my research. It would be great to collaborate with Guo and others in this regard. I hope I can help them in their goals as well.

SM: Please give us your thoughts and responses to the art shown in this issue and the interview between Guo Haiping and Chen Shushan.

DW: The interview between Guo Haiping and Chen Shushan was enlightening and the most informative thing I have read about such art in China. I am appreciative of Guo Haiping’s unique mind and amazed by his personal journey through art, psychology, counseling, art therapy and now outsider art. His description of the studio situation in China and notions of mutual help are fascinating and I support his efforts. Overall, I am extremely impressed with his approach and agree with the perspectives presented; this is quite utopian – I like it. It is interesting that there seem to be such similarities in our views from across the world – and with no previous awareness or contact between us. I think his perspective and his thoughts about also including views on outsider art beyond Europe and North America are extremely important here. I embrace his statements about how such art is evidence of a common humanity and the creative imagination. I find the art fascinating and I like the way it is discussed, because it includes a consideration of artists’ views, personal situations, cultural ecology, history and other contexts.

SM: Can you say more about the utopian aspect of Guo’s vision? Is it both aspirational and possible to realize in a practical sense?

DW: As I understand it, Guo’s vision is to transform the understanding of outsider art as well as the treatment of the artists and to encourage the acceptance of their achievements within broader society. In this way he intends to transform societal views and values in a utopian and inclusive manner that is very grounded and practical. This is a noble goal and I am with him – heart and soul. In China, he already has transformed the situation in hospitals for individuals – with a greater acceptance of the importance of art studios and an increased societal understanding of the aesthetic accomplishments of people with mental health challenges. His pioneering vision hopefully can be connected to a greater global movement to integrate those individuals who are “differently-abled” into broader society and to help everyone appreciate their unique contributions and abilities that are so often devalued or ignored.

SM: I am very interested in your perceptions concerning what you say about “evidence of a common humanity and the creative imagination” manifested worldwide in “outsider art” both in relation to the paintings shown here and what Guo says about the contexts within which the artists work.

DW: I agree with Guo’s emphasis on contexts and culture ecology; absolutely. We might need to discuss the idea of shared “universal qualities” in order to get more specific about his intention. There are many common features but there is also a uniqueness to each artist, their artwork and context. I am not sure about what Guo describes as “common atavistic memories” but he may be able to convince me. We need to meet and discuss. His idea of “free and flexible views” makes sense and I would like to hear more.

In terms of common and universal impulses and reducing my view to its essentials, I would say that art (as a form of self-expression) is the purposeful manipulation of materials to create order- sometimes out of chaos. The ability to express oneself in a meaningful way and to manipulate materials into some sort of order has various functions; importantly, this can often be therapeutic in one way or another.

I do believe that human beings have a universal urge to create and a desire to perfect forms. We see that repetition is important – as are distorted and abstract forms of expression – whether among self-taught artists, indigenous artists or contemporary art school trained artists. However, the works of the self-taught outsider artists often are two dimensional and not concerned with (or aware of) conventional approaches to visual perspective. I have noticed that mandala-like designs seem to appear frequently – am I imagining it or perhaps we need to consult Carl Jung here?

What I find compelling about such art is that it is not constrained by – or imitative of – conventional notions of mainstream art or global art trends. Such art reflects personal needs and experiences as well as vernacular culture – and although it engages with culture, it is also idiosyncratic and innovative in some way. This is the enduring appeal of such art – as these self-taught artists are art movements of one person; individuals, pursuing and expressing their visions in unique and compelling ways.

SM: Do you have suggestions and ideas about future worldwide cooperation and how people in different regions can work together? Are there ways that a global effort might support the individual artist? Or do you think there is a certain value in isolation with regard to supporting the uniqueness of each artist, what you call the “lone” movement “of one person”? Whether there might be a mix of both?

DW: I like the idea of global collaboration. I think there should be more support for art studios for individuals with disabilities, but how? I would like to see some sort of international conference where people could meet and discuss such art and all the related issues. The question of the relative isolation of the artist is provocative, but I think Guo is correct in this regard. For certain individuals who cannot be integrated into society, it might be better to create a supportive community that fosters creativity but also allows interaction with the broader society.

SM: I think our readers will also be interested to know whether you have any cautions since both you and Guo express how easy it is to misperceive the art and artists and appropriate the work for purposes that may not serve their interests.

DW: Well, yes, such art can be and will be misperceived. In some cases, as has happened in the past, the artists will be exploited and harmed. I am critical of the concept of the “outsider” because of its negative connotations; for some this implies insanity, a lack of culture or ignorance, etc. Just recently, I have been criticized for my views by one outsider art enthusiast who is invested in the outsider art term, and there really are some people who view the outsider label as the best way to promote and sell the art. I understand their desire for a good marketing term, but then I begin to wonder if they are just too insensitive or too money-hungry to understand the problematic nature of the term? I explain all of this in my book. Those who are financially invested in the field often say that they are tired of such “term warfare.” I don’t want to belabor it further here, but I purposely emphasized the problems of the term ‘outsider’ which some artists that I interviewed find offensive or even racist in the case of African American artists. In conclusion, I advise anyone who uses the label outsider art to put it in quotes as “outsider art,” to clarify what you mean by the term and to acknowledge some of its negative connotations. And then move on from there.

SM: What has this work with outsider art taught you about the human condition? About the purpose of artistic expression? Has it changed you as a person?

DW: This is good – you ask a profound and personal question here. I appreciate it. To say it loud and clear; my study of outsider art has transformed me in ways I could not imagine. It has given me faith in the power of art – in its healing and life-enhancing aspects. But even more than this: in dark times, in the worst of times (as I discuss in the book) I have learned that people somehow summon the strength to express themselves – to save themselves and others – in remarkable ways. This is inspiring and in some cases unbelievable. My research and writing the book renewed my faith in humanity and gave me an understanding of art as being essential to human well-being and fulfillment. I am still learning about the redemptive power of art. I hope I can share more of the absolute importance of the creative process with others in the future.

About the authors

Daniel Wojcik is Professor of English and Folklore Studies at the University of Oregon. In addition to Outsider Art: Visionary Worlds and Trauma, his books include Punk and Neo-Tribal Body Art; The End of the World as We Know It: Faith, Fatalism, and Apocalypse in America; and The Visionary Art of Ionel Talpazan (forthcoming). Email: dwojcik@uoregon.edu

Shaun McNiff, University Professor, Lesley University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Email: smcniff@lesley.edu